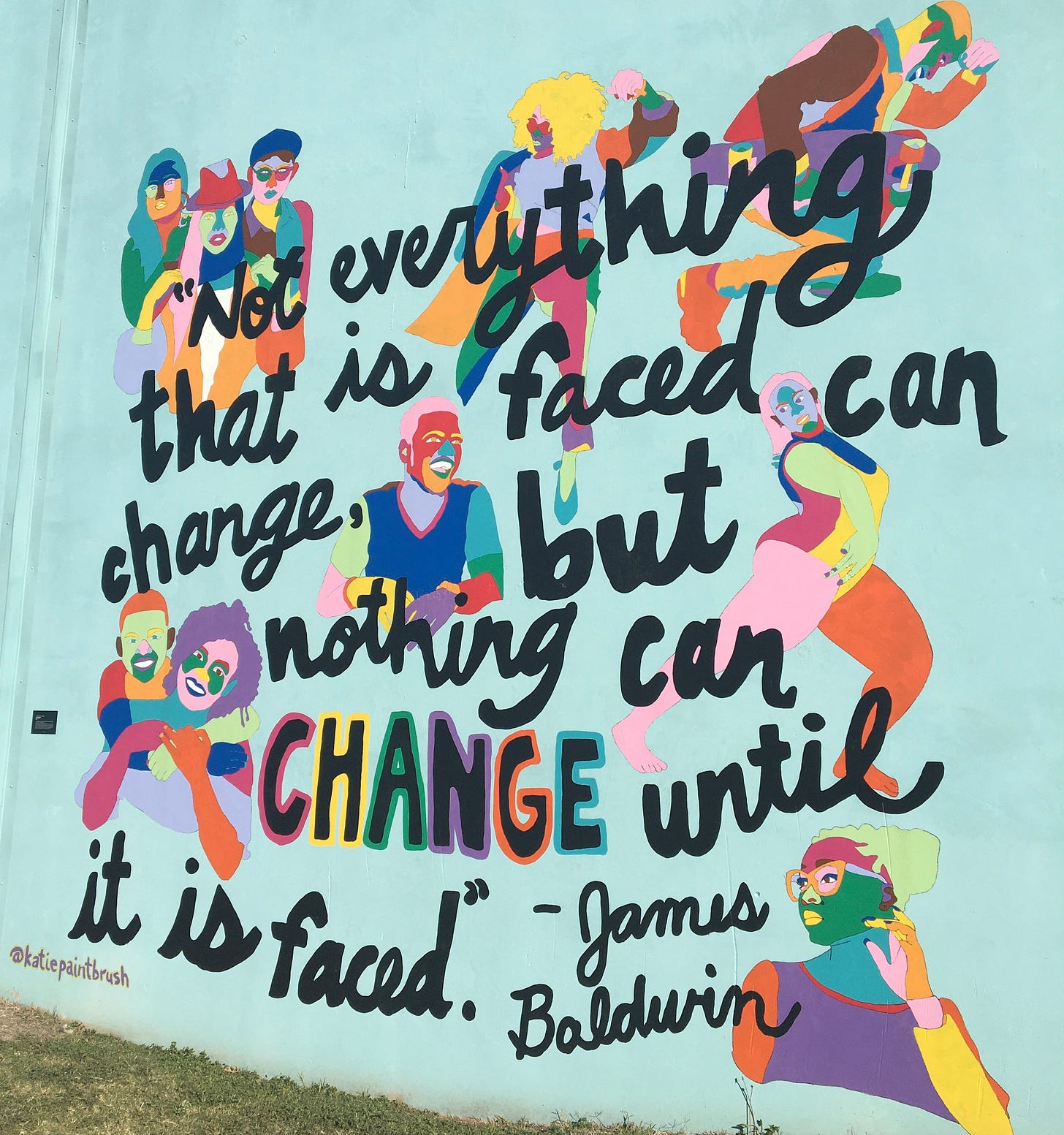

Defy Archaic Power Structures

Resident planners shake up the traditions that limit us.

Across America, we are dotted with once-boomtown-cities that now face the challenges of recovering their economies, rehabilitating their land, and recreating their identities. Railroad, mill, and factory moguls quashed civic life by enacting their power upon local governments and milking their communities dry of its resources for their own gain. Whole t…